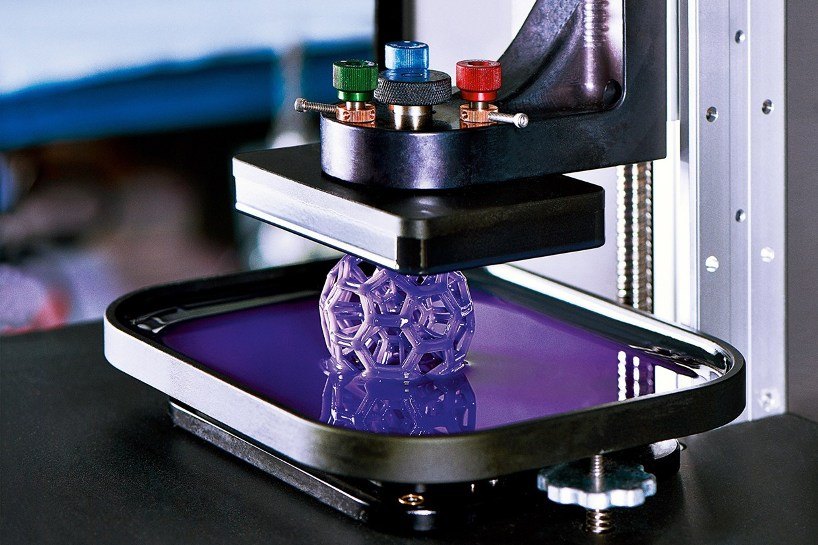

CC image courtesy of Lifehack

By Bradley Cho

Introduction

The rapidly growing field of Three Dimensional Printing Technology (3D Printing) has ushered in what many have heralded as a new golden age of creative manufacturing.[1] From the medical field—where doctors in the United Kingdom have designed 3D-printable implants for trauma patients[2]—to engine parts for some of the most powerful automobiles in the world,[3] 3D Printing is becoming an essential utility for small and large manufacturers alike. In his 2013 State of the Union Address, President Barack Obama characterized the technology as a manufacturing boon that “has the potential to revolutionize the way we make almost everything.”[4]

The 3D Printing State of Affairs

At its core, 3D Printing is the process of creating items through a process called “Additive Manufacturing.” In contrast to the more traditional process of “Subtractive Manufacturing,” where materials are cut and shaped through tools such as drills or lasers, “Additive Manufacturing” builds 3D objects by adding ultrathin layers of materials, which can range in scope from plastic to living tissue.[5] This process allows the creation of complex objects with little more than a single 3D printer and “Computer Assisted Design” (CAD) software files that can store information about the surface geometry of virtually any three-dimensional object.[6]

In terms of costs, 3D Printing technology costs have dropped dramatically as key patent protections related to such technology have recently expired. In 2008, a key 3D Printing patent for “Fused Deposition Modeling” (FDM) expired,[7] while the patent for “Selective Laser Sintering” (SLS) expired in 2014.[8] However, this cost drop and the technology’s proliferation have also raised international fears about whether such information should be tightly regulated—and even fundamentally—how much free speech protection should be afforded to publically available and potentially dangerous designs.[9] For instance, in 2013, a law student at the University of Texas generated significant controversy when he successfully manufactured a working firearm using a basic 3D printer.[10] The CAD design file was downloaded over 100,000 times in just two days—much of it from countries that ban gun ownership.[11] While personal gunsmithing is not a prohibited activity in the United States, foreign jurisdictions across the globe with tighter gun control laws have expressed significant concern over the proliferation of such information from the United States.[12] As global access to 3D printing continues to grow exponentially, this is certain to be a novel legal battleground where countries with vastly different national philosophies will disagree over how such information should be controlled.

The Current Online Copyright System

At least in the United States, copyright-protected digital content can be removed from websites through a system governed under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).[13] For instance, if a copyrighted song is uploaded to a website such as YouTube, a copyright holder who believes that the upload is infringing can file a “takedown” request with the website.[14] The uploader can then either accept the takedown, or challenge the copyright holder’s claim. If neither party can reach a compromise, the copyright holder has the option to take the uploader to court.[15]

In the world of 3D Printing, the ability to copyright digital CAD files becomes enormously murky.[16] 3D Printing technology has particularly been embraced by individuals and organizations dedicated to free and open-source software.[17] Catherine Jewell at the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has called 3D printing an important mark in the “democratization” of manufacturing.[18] The European Parliamentary Research Service has commented that this technology is likely to have serious implications for existing IP regulations, for copyrights, patents, and trademarks alike.[19]

Unlike international laws covering copyrighted materials, no formal international legal framework currently exists to prohibit or regulate what are essentially open-source designs over the Internet.[20] The manufacturing of prohibited items such as of 3D-printed guns is clearly banned in jurisdictions like the European Union.[21] However, these countries have very little authority over the spread of such information from outside their borders. In the case of the University of Texas student who freely and publically uploaded his gun designs onto the Internet, it was the U.S. Department of State—not a domestic law enforcement agency or regulatory body—that requested that his designs be removed from an Internet website.[22] In doing so, the State Department cited compliance concerns under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), a statute originally conceived to ban the export of national-scale defense articles outside of the United States.[23] Although the State Department’s approach was ultimately vindicated by a narrow majority in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals based on a “very strong public interest,”[24] the dissenting judge called such a decision an “irrational representation” of export regulations.[25]

Notwithstanding, and despite the State Department’s protracted legal struggle to ban a single plastic gun design off a website, hundreds of non-copyrighted 3D-printed firearm designs—many significantly improved over their original predecessor—have since flooded the internet.[26] As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held in ClearCorrect v. International Trade Commission, publically available 3D CAD designs are not themselves violations under current law—meaning that existing frameworks, both foreign and domestic, are inadequate for regulating such developments.[27] International legal cooperation, in regulating potentially dangerous 3D CAD designs, will also likely gain very little traction.[28] Such widespread cross-border jurisprudential cooperation has only ever existed against universally reviled activities such as child pornography; and the major legwork of regulating such technology will necessarily have to come from domestic legal frameworks.[29]

As the 3D printing industry matures, it is clear that regulating bodies across the world will address the risks and challenges of such technology. Some commenters have suggested modifying current copyright law as a method to limit the manufacturing of such dangerous items.[30] Such tactics, however, have already proven highly impractical in a similar field: in combating the illegal distribution of copyrighted content music through file-sharing platforms like BitTorrent.[31] The development of 3D Printing technologies—and the potential dangers they pose—highlight the significant limitations inherent in modern day cross-border, international regulatory frameworks in dealing with such developments.

Conclusion

As 3D printing technology grows in prominence while the ease of transmitting such information increases, the regulation of such information presents both unique opportunities and challenges. Nation-states possess vastly different regulatory frameworks and philosophies on the development, creation, and possession of various goods and products within their borders. As the ongoing 3D-printed firearm controversy demonstrates, existing international legal frameworks are uniquely unsuited to the task of controlling the flow of such information. Such publically available designs tend to be uncopyrighted and open-source, rendering them unassailable to cross-border copyright and intellectual property challenges. While domestic regulation—coupled with sporadic international cooperation—may provide a partial solution to such concerns, a time may soon come when nations must fundamentally rethink the legal mechanisms that will harness what some have come to call the “Third Industrial Revolution.”[32]

*Bradley Cho is a J.D. candidate at Cornell Law School where he is a Cornell International Law Journal Associate. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree from Yale University.

[1] See Heidi Nielson, Manufacturing Consumer Protection for 3-D Printed Products, 57 Ariz. L. Rev. 609, 611–12 (2015) (stating current revolutions and developments in 3D printing technology).

[2] Luke Dormehl, New 3D-Printing Software Allows Surgeons to Quickly Design Titanium Facial Implants, Digital Trends (Nov. 2, 2016, 12:21 PM), http://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/titanium-implants-3d-printing/.

[3] Joseph Young, Aston Martin to Use 3D Printing for its Most Powerful Engine Yet, 3DPrint.com (Nov. 2, 2016), https://3dprint.com/154211/aston-martin-to-use-3d-printing/.

[4] President Barack Obama, State of the Union Address (Feb. 12, 2013) (transcript available at

http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/02/12/remarks-president-state-union-address).

[5] Henry Fountain, At the Printer, Living Tissue, N.Y. Times (Aug. 18, 2013), http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/20/science/next-out-of-the-printer-living-tissue.html?_r=0.

[6] Matt Petronzio, How 3D Printing Actually Works, Mashable (Mar. 28, 2013), http://mashable.com/2013/03/28/3d-printing-explained/#rSS9YjsIPkqL.

[7] Paul Gillin, 3-D Printing’s “Pied Piper” Foresees Innovation Surge as Patents Expire, SiliconAngle (July 20, 2016), http://siliconangle.com/blog/2016/07/20/3-d-printings-pied-piper-foresees-innovation-surge-as-patents-expire/.

[8] Id.

[9] See Rory K. Little, Symposium: Guns Don’t Kill People, 3D Printing Does? Why the Technology is a Distraction From Effective Gun Controls, 65 Hastings L.J. 1505, 1508 (2013–2014) (“I think it best to address gun control in this context by imagining that the technology has become perfect: home 3D printers will only have to wiggle their noses and the objects they imagine—guns and all—will quickly appear.”).

[10] Casey Chan, The World’s First Entirely 3D Printed Gun, Gizmodo (May 3, 2013, 11:00 PM), http://gizmodo.com/the-worlds-first-entirely-3d-printed-gun-489975583.

[11] Andy Greenberg, 3D-Printed Gun’s Blueprints Downloaded 100,000 Times in Two Days (With Some Help from Kim Dotcom), Forbes (May 8, 2013, 5:12 PM), http://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2013/05/08/3d-printed-guns-blueprints-downloaded-100000-times-in-two-days-with-some-help-from-kim-dotcom/#34bac8be88c6.

[12] Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Firearms and the internal security of the EU: protecting citizens and disrupting illegal trafficking, COM (2013) 716 final (Oct. 21, 2013), http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/organized-crime-and-human-trafficking/trafficking-in-firearms/docs/1_en_act_part1_v12.pdf (“[C]hallenges posed by the potential for 3D printing of weapons and ammunition.”).

[13] Rebecca Alderfer Rock, Comment, Fair Use Analysis in DMCA Takedown Notices: Necessary or Noxious?, 86 Temp L. Rev. 691, 692–93 (2014) (“[D]escribing the DMCA as a compromise between ISPs and the copyright industry . . . to deal with infringement issues on the web.”).

[14] Submit a Copyright Takedown Notice, Google, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2807622?hl=en, [http://perma.cc/Q4A4-X7J7] (last visited Nov. 9, 2016).

[15] Id.

[16] Maya M. Eckstein & Eric J. Hanson, Open source opens many licensing issues for 3D printing, Embedded Computing Design (June 27, 2016), http://embedded-computing.com/articles/open-source-opens-many-licensing-issues-for-3d-printing/ (describing the development and issue of both 3D open source “software” and “hardware”).

[17] See, e.g., Brian Rideout, Printing the Impossible Triangle: The Copyright Implications of Three-Dimensional Printing, 5 J. Bus. Entrepreneurship & L. 161, 163 (2012) (describing the open source 3D printing community).

[18] Catherine Jewell, 3-D Printing and the Future of Stuff, WIPO Magazine (Apr. 2013),

http://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2013/02/article_0004.html.

[19] Legal Aspects of 3D Printing, Eur. Parliamentary Res. Serv. (Mar. 17, 2014), https://epthinktank.eu/2014/03/17/legal-aspects-of-3d-printing/ (noting their potential impact on the general principles of intellectual property).

[20] See International Authority & Recognition, Open Source Initiative, http://opensource.org/authority (last updated Dec. 2015) (listing nations across the world that have recognized Open Source initiatives, but no unified framework governs their use across international borders).

[21] Nadia Gilani, Gun factory fears as 3D blueprints available online, Metro.co.uk (May 6, 2013, 10:00 PM), http://metro.co.uk/2013/05/06/gun-factory-fears-as-3d-blueprints-available-online-3714514/ (“[A]nyone creating a gun of this type in Britain would need a firearm licence or risk a prison sentence of up to five years.”).

[22] Andy Greenberg, State Department Demands Takedown Of 3D-Printable Gun Files For Possible Export Control Violations, Forbes (May 9, 2013, 2:36 PM), http://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2013/05/09/state-department-demands-takedown-of-3d-printable-gun-for-possible-export-control-violation/#1f3938633fb7.

[23] Id.

[24] Def. Distributed v. U.S. Dep’t of State, 838 F.3d 451 (5th Cir. 2016); see also Cyrus Farivar, Court: With 3D Printer Gun Files, National Security Interest Trumps Free Speech, ARSTechnica (Sep. 21, 2016), http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2016/09/court-groups-3d-printer-gun-files-must-stay-offline-for-now/.

[25] Id.

[26] Perry Chiaramonte, Powerful 3D-printed Rifle Fires NATO Rounds, Fox News (Mar. 30, 2015), http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2015/03/30/powerful-3d-printed-rifle-fires-nato-rounds.html (describing the recent upload of designs capable of firing 5.56 and 7.62 millimeter military-grade ammunition on PrintedFirearm.com, a website devoted to 3D gun printing).

[27] ClearCorrect v. International Trade Commission, 810 F.3d 1283 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 10, 2015). Here, the Federal Circuit ruled that the ITC has no jurisdiction over digital data, including 3D printing files, transmitted into the United States from abroad because they cannot be considered “material things.”

[28] See e.g., Paul M. Schwartz, The EU-U.S. Privacy Collision: A Turn to Institutions and Procedures, 126 Harv. L. Rev. 1966 (2013) (outlining the broad collisions over information technology privacy doctrine between the United States and the European Union, generally highlighting how collaboration is difficult among entities with divergent national philosophies).

[29] Tabrez Y. Ebrahim, 3D Printing: Digital Infringement & Digital Regulation, 14 Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 37, 66 (2016) (discussing U.S.-based proposed Congressional regulations).

[30] Katie Fleschner McMullen, Worlds Collide When 3D Printers Reach the Public: Modeling a Digital Gun Control Law After the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, 2014 Mich St. L. Rev. 187, 216 (2014) (analyzing how the 3D printing of weapons can be regulated with help from the DMCA).

[31] Andres Sawicki, Comment, Repeat Infringement in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, 73 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1455, 1485 (2006) (stating “[t]he problem of online copyright infringement is complex, and the DMCA is undoubtedly inadequate to address it in its entirety”).

[32] Filemon Schoffer, Is 3D Printing The Next Industrial Revolution?, TechCrunch (Feb. 26, 2016), https://techcrunch.com/2016/02/26/is-3d-printing-the-next-industrial-revolution/.