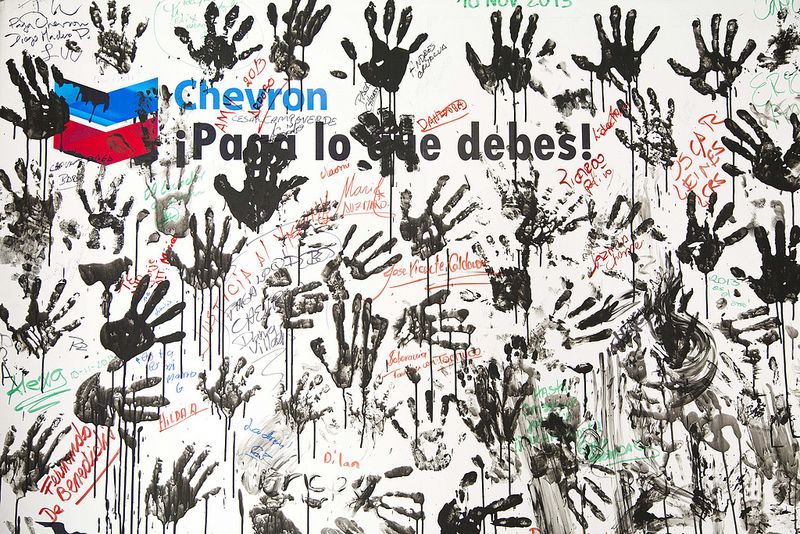

CC Image Courtesy of Cancillería Ecuador

Lago Agrio: The Bitterness of a Judgment

by Oscar Lopez*

Introduction

Deep in the Ecuadorian jungle, sitting along the shores of the Aguarico River, sits Lago Agrio.[1] This city, with a population of seventy thousand, serves as the main port for the Amazonian basin and provides the only link to Ecuador’s most remote jungles.[2] Once a prosperous area for oil drilling, the city’s name, Sour Lake, now fittingly describes its state.[3] The once rampant industry has turned the area into a wasteland where the population suffers from elevated rates of disease; the farmland is poisoned; and the water is heavily contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons and toxic heavy metals.[4]

Many Ecuadorians have claimed that Texaco’s indiscriminate dumping of toxic wastes created this condition.[5] Texaco, through its subsidiary TexPet, was involved in oil exploration in the area from 1964 to 1992.[6] These citizens have alleged that TexPet improperly dumped toxic by-products of the drilling process into the river, burned toxic substances, dumped by-products into landfills, and spread by-products over dirt roads.[7] Furthermore, they have claimed that TexPet’s trans-Ecuadorian pipeline leaked massive amounts of petroleum into the environment.[8] As a result of a quarter-century of pollution, an entire generation now suffer from a myriad of physical injuries, including voice loss, birth defects, precancerous growths, and other unknown illnesses.[9]

In 1993, a group of affected Ecuadorians brought suit seeking money damages and cleanup for the region.[10] Since 1993, Texaco and Chevron—who bought Texaco in 2001 and assumed its liabilities—have been involved in a fierce legal battle with these plaintiffs.[11] In February 2011, a court in Lago Agrio rendered an $18 billion judgment against Chevron for the alleged contamination.[12] In response, Chevron has appealed that decision twice. However, on November 12th of this year, the Ecuadorian National Court of Justice put the case to rest by partially upholding the lower court’s decision.[13] On review, Ecuador’s highest court found Chevron liable for $9.5 billion in damages, about half of the lower court’s award.[14]

Many Ecuadorians hope the recent judgment will mean the end of this twenty-year legal battle. But will the plaintiffs in this case, along with their lawyers, see Chevron pay? Maybe not. Despite the recent decision, the Ecuadorian court’s judgment may not be enforceable against Chevron’s assets in other countries. Moreover, even if the judgment is enforceable, the country of Ecuador may have to reimburse Chevron for the amounts it pays to satisfy the judgment.

Judge and Lawyer Misconduct

Soon after the court in Lago Agrio rendered the initial judgment against Chevron, the company filed a suit against the Ecuadorian plaintiffs and their counsel, Steven Donziger, in the Southern District of New York (SDNY). The case, which is still pending, is partly based on the defendants’ violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act.[15] In the case, Chevron contends that the Lago Agrio judgment is not enforceable outside of Ecuador because it was fraudulently obtained.[16]

Most of the evidence of misconduct stems from the filming of Crude, a documentary which Donziger wanted created to show the struggle of Amazonian natives.[17] In the film, Donziger is allegedly seen pressing Ecuadorian judges to rule in his favor, a tactic he himself admits would never fly in the U.S.[18] Donziger is also seen influencing the supposedly neutral expert witnesses tasked with assessing Lago Agrio’s contamination.[19] Finally, the film depicts a representative of the plaintiffs informing Donziger that he had left the office of President Correa “after coordinating everything,” to which Donziger declares, “Congratulations. We’ve achieved something very important in this case . . . . Now we are friends with the President.”[20]

As part of the ongoing Donziger suit, Chevron also called Ecuadorian Judge Nicolas Zambrano Lozada as a witness.[21] Chevron argues that Zambrano, who presided over the Lago Agrio litigation, was not the person who authored the $18 billion opinion in the case.[22] Instead, the company contends that Zambrano let the plaintiffs author the Lago Agrio opinion in exchange for $500,000 that was to come from the eventual recovery from Chevron.[23]

Zambrano’s testimony has been particularly damning for the Donziger defendants. During the examination, Chevron’s counsel asked Judge Zambrano a series of questions about the opinion he supposedly wrote. Zambrano’s answers, however, made it appear that he had never even read the opinion.[24]

In response to counsel’s questions, Zambrano was unable to recall a host of critical elements in the decision, including the theory of causation, the most powerful carcinogenic agent involved, or what “TPH,” a term repeatedly used throughout the decision, stood for.[25] Moreover, when asked how he was able to cite cases from English and French courts—he admittedly spoke neither—Zambrano responded that he relied on an online translator.[26] The most damaging part of the testimony, however, was that Judge Zambrano was unable to explain how long portions of internal memos between Lago Agrio’s lawyers were used in his opinion.[27]

The evidence from Crude along with Judge Zambrano’s testimony makes a decision in favor of Chevron a likely outcome. Moreover, if the court finds that the Lago Agrio judgment was the product of fraud, the judgment will be unenforceable in the U.S.[28] and most other jurisdictions where Chevron has assets.[29]

Ecuador’s Violation of Its Bilateral Trade Agreement with the U.S.

Even if the judgment is enforceable, Ecuador may have to reimburse Chevron for satisfying it. In addition to the litigation in the SDNY, Chevron has also engaged Ecuador before The Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration for violations of Ecuador’s bilateral trade agreement with the United States and for violations of an agreement the country made with Texaco in 1998.[30] Chevron’s action, which was first brought in 2009 at the beginning of the Lago Agrio litigation, alleges that Ecuador released Texaco from all liability relating to its previous operations in the country.[31]

According to Chevron, TexPet signed a minority partnership agreement with Petroecuador—Ecuador’s state oil company—to perform exploration and production in Ecuador for a period of twenty years.[32] At the end of this concession in 1992, several Ecuadorian authorities audited the area and determined that TexPet needed to conduct environmental remediation in proportion to its one-third ownership of the venture.[33] Accordingly, Texaco spent over $40 million rehabilitating the area and constructing public works throughout the region, all under supervision of the Ecuadorian government.[34] Chevron alleges that in 1998, after the government found the cleanup fully satisfactory, it released TexPet of all claims, liabilities, and obligations associated with that concession agreement.[35] Thus, because TexPet has had no involvement in any operations in Ecuador since 1992,[36] any remaining cleanup or damages resulting from oil operations are Petroecuador’s responsibility.

The arbitration panel has previous stated that should Chevron prevail in arbitration, “any loss[es] arising from the enforcement of [the Lago Agrio] judgment (within and without Ecuador) may be losses for which [Ecuador] would be responsible to [Chevron] under international law.”[37] And since the beginning of the action, the panel has handed down a series of awards favoring Chevron.[38]

However, Chevron’s victory is not guaranteed. In its most recent partial award, the panel established the validity of the release agreement between Ecuador and Texaco but noted that the agreement recorded “an intention by the signatory parties not to affect claims made separately by other third persons” and that under Ecuadorian law the agreement could not “affect those separate third-person rights.”[39] Thus, the panel could find that the Lago Agrio plaintiffs’ claims were valid and not released by the agreement. As a result, Ecuador would not be liable to Chevron.

Conclusion

Between the two ways that Chevron could dodge the Lago Agria judgment, the Donziger case seems the more likely route. A Chevron win would effectively bar Ecuador’s ruling against Chevron, as most countries where Chevron has assets would not validate a judgment ridden with fraud.[40] As the evidence against Donziger mounts, and as he concedes that the he may have made some mistakes along the way, Donziger’s only defense has been the assertion that fraud and coercion are just normal practices in Ecuador.[41]

Unfortunately, the real victims here are the environment and the residents of Lago Agria.[42] Whether it was TexPet’s fault or Petroecuador’s, the region and its people have suffered irreparable harm and deserve a better fate than the greed-polluted litigation that their potential award rests on.

For a PDF of this article in formal, law-journal format, click here.

Citation: Oscar Lopez, Lago Agrio: The Bitterness of a Judgment, 1 Cornell Int’l L.J. Online 103 (2013).

* Oscar Lopez is a J.D. candidate at Cornell Law School, where he is the Cornell International Law Journal’s Associate on South American Affairs. He holds an M.B.A. from Texas Tech University and a B.A. in economics and Spanish from the University of Texas at Austin.

[1] See Lago Agrio Introduction, Frommer’s, http://www.frommers.com/destinations/lago-agrio/276667 (last visited Nov. 21, 2013).

[2] See id.

[3] See id.

[4] See Thomas P. DiNapoli, What Chevron Owes the People of Lago Agrio, Huffington Post (Sept. 26, 2011, 4:47 PM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/thomas-p-dinapoli/chevron-ecuador-lawsuit_b_981638.html; $27 Billion Damages Assessment, Chevron Toxico, http://chevrontoxico.com/about/historic-trial/27-billion-damages-assessment (last visited Nov. 21, 2013).

[5] See Jota v. Texaco Inc., 157 F.3d 153, 155–56 (2nd Cir. 1998).

[6] Id.

[7] Id. at 155.

[8] See id.

[9] See id. at 156; Ecuador Oil Contamination Spawns Turmoil at Chevron Annual Meeting, Environmental News Service, http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/may2010/2010-05-26-092.html (last visited Nov. 21, 2013).

[10] Jota, 157 F.3d at 155.

[11] See Texaco Petroleum, Ecuador and the Lawsuit Against Chevron, Amazon Post (June 2, 2009), http://www.theamazonpost.com/about-the-amazon-post/texaco-petroleum-ecuador-and-the-lawsuit-against-chevron.

[12] See Patrick Radden Keefe, Reversal of Fortune, New Yorker (Jan. 9, 2013), http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/01/09/120109fa_fact_keefe?currentPage=all.

[13] See Alexandra Valencia, Ecuador High Court Upholds Chevron Verdict, Halves Fine, Reuters (Nov 13, 2013), http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/11/13/us-chevron-ecuador-idUSBRE9AC0YY20131113.

[14] Id. See also Ecuador Asks Arbitration Court to Dismiss Chevron Case, Agencia EFE (Nov. 16, 2013, 1:00PM), http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/agencia-efe/131116/ecuador-asks-arbitration-court-dismiss-chevron-case.

[15] See Chevron Corp. v. Donziger, 768 F. Supp. 2d 581, 625 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).

[16] See id. at 625–26.

[17] Id. at 595.

[18] Id. at 604.

[19] Id.

[20] Id. at 604–05.

[21] Roger Parloff, Disastrous Day for the Lago Agrio Plaintiffs in Chevron Trial, CNN Money (Nov. 6, 2013 9:04PM), http://features.blogs.fortune.cnn.com/2013/11/06/lago-agrio-chevron-trial/.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] See id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] See, e.g., Bank Melli Iran v. Pahlavi, 58 F. 3d 1406, 1410 (9th Cir. 1995) (“It has long been the law of the United States that a foreign judgment cannot be enforced if it was obtained in a manner that did not accord with the basics of due process. . . . ‘A court in the United States may not recognize a judgment of a court of a foreign state if: (a) the judgment was rendered under a judicial system that does not provide impartial tribunals or procedures compatible with due process of law . . . .’”).

[29] See Ralf Michaels, Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law 7 (2009), available at http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2699&context=faculty_scholarship (“If the judgment was based on fraud or abuse of process, recognition will usually be denied.”). But see Daniel Fisher, Donziger Vows ‘Redress’ Against Chevron, While Admitting ‘Errors Along the Way’, Forbes (Nov. 15, 2013, 2:58PM), http://www.forbes.com/sites/danielfisher/2013/11/15/donziger-vows-redress-against-chevron-while-admitting-errors-along-the-way/.

[30] See Ecuador Asks Arbitration Court to Dismiss Chevron Case, supra note 14.

[31] See First Partial Award on Track I, Chevron v. Ecuador, PCA Case No. 2009-23, at 16–23 (Sept. 17, 2013) (outlining Chevron’s claims), available at http://www.theamazonpost.com/wp-content/uploads/chevron-ecuador-bit-tribunal.pdf.

[32] See History of Texaco and Chevron in Ecuador, Chevron, http://www.texaco.com/sitelets/ecuador/en/history/ (last visited Nov. 21, 2013).

[33] See id.

[34] See id.

[35] See id.

[36] See id.

[37] Procedural Order and Further Order on Interim Measures, Chevron v. Ecuador, PCA Case No. 2009-23 (Jan. 28, 2011), available at http://www.chevron.com/documents/pdf/ecuador/ProceduralOrderandFurtherOrderonInterimMeasures.pdf?.

[38] See Ecuador Lawsuit, Chevron, http://www.chevron.com/ecuador/#b2 (last visited Dec. 12, 2013).

[39] See First Partial Award on Track I, Chevron v. Ecuador, PCA Case No. 2009-23, at 40–41 (Sept. 17, 2013).

[40] See Michaels, supra note 29.

[41] Clifford Krauss, Lawyer Concedes Mistakes in Chevron Case, N.Y. Times (Nov. 13, 2013), http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/14/business/energy-environment/lawyer-concedes-mistakes-in-chevron-case.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1.

[42] Paul M. Barrett, Amazon Crusader. Chevron Pest. Fraud?, Bloomberg BusinessWeek (Mar. 9, 2011), http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/11_12/b4220056636512.htm#p2.